| Jul/Aug 2010 • Travel |

| Jul/Aug 2010 • Travel |

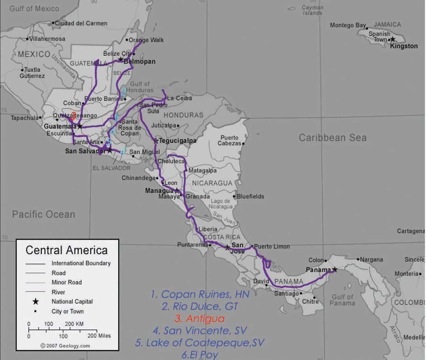

Sick from technology overdose, I took my first backpacking trip through Central America with my older sister Nastassia, herself a veteran backpacker. Her extensive background in "roughin' it" and my own lack of experience made her very mothering. It started at the airport when she tied all the straps of my pack together for me. We had very different conceptions of travel. I wanted this trip to be spontaneous; I didn't buy a guidebook, and I didn't learn Spanish. The only comfort I offered my worried friends and family regarding my itinerary, budget, or survival skills was, "I'll just wing it." But Nastassia had drafted a travel program, listing all the sights in Guatemala and around. She could speak Spanish, and she was pro light packer; her towel was a small quick-dry travel specimen, which she had trimmed down even further to the size of a table napkin. So I proclaimed myself the buffoon of this duo dynamic. But, I figured it wouldn't be so bad. I'd be taken care of without having to bother about any of the responsibilities. Hell, I just handed her my money and told her it would be easier if she just took care of everything. But while I enjoyed seeing all that Guatemala had to offer, going through Belize and even catching a glimpse of the Copan Ruins in Honduras, I missed out on the best part of traveling: being involved in your own discoveries.

Nastassia left me in Antigua, Guatemala, after 21 days, to trek the Canadian hills of Vancouver. My travel childhood was over. I had to take control of my trip. The first order of business was to fix my financial SNAFU. I had left the United States with the very misguided notion that I could breeze through Central America with just one thousand dollars. After three weeks, alas, I had depleted half my funds. We hadn't been spoiling ourselves, either. Most of our money was spent on transportation and border taxes. We stayed at budget hostels and ate mainly street food to get by. When we were in Belize, where the average price of coffee was four Belize dollars (about $2 U.S.), we survived on bananas and saltine crackers. So there was no way, even by being careful, that I could continue my way down south for two more months. I had to find a job. Since I still didn't speak much Spanish, I tried my luck at an Irish pub. It wasn't hiring, but the bar next door was looking for a bartender. I walked into the Arabian-themed hookah bar and was hired immediately.

I wasn't making a fortune, but 100 quetzals a night (around $12.50) was higher than the average bartender wage in Antigua. On top of being able to get by again, I learned a tremendous amount of Spanish on the job. The first three days were brutal. I was speaking a mix of French, Italian, and Spanish. But after the first week, I was holding conversations, albeit with some difficulty.

Little by little, I managed to infiltrate the local lifestyle. I moved into a house with three locals, I made tortillas and beans everyday, and I hand-washed my clothes in the courtyard basin. I even got mugged, just like a local, a week after I established myself in the fair little town. After work, I walked home with César, my effeminate roommate and co-worker, when the two muggers approached us with the pretense of being on a booze hunt. I had no money, no cell-phone, but unfortunately I did have my iPod. And while César emptied his bag, I somehow thought it would be best to hang on to my new iPod. Even though I knew it would be smarter just to hand it over, my hand gripped on to it and wouldn't let go. I resisted the mugger's attempt to extract it from me by letting him have my wind-up flashlight as a diversion. Luckily, a minute later, his accomplice called him up to evacuate the crime scene. I couldn't believe I still had that damned iPod! César's shaking body collapsed into mine as he exclaimed in a high-pitched voice—and in English for some reason—"thank God we are alive!" The whole thing felt surreal. Everyone had warned me to be careful at night and not to walk alone, and the one night I was accompanied by someone, the inevitable happened. When César suggested we go to the police, I was less than thrilled to prowl around looking for them and risk losing what had miraculously stayed in my possession.

When we found the police, César described the assault in an outraged tone and his usual exaggerated mannerisms. We climbed in their car after finding his empty wallet in one of the streets perpendicular to the one we got robbed on. I thought it was ridiculous to go on a robber hunt some 20 minutes after the facts happened. And just as I thought to mention we were wasting our time, César leaned over to my side of the car, pointed at two men in the streets and whispered dryly, "Ellos son!" I didn't recognize them as the culprits. They were wearing sweaters, while our men wore light t-shirts. But the police stopped and frisked them immediately after César's cathartic identification. He was now burying his face in his sweater's hood, deforming his handsome dark features into a prominent surface of wrinkles. He begged the police not to let the two men look at him. I thought he was overreacting, and I was laughing at him up until they brought his phone and my flashlight. The joke was over. Anger settled in. I asked one of the policemen if I could beat up the guy. With a wide grin, the man of the law instantly opened the car door and said, "Con mucho gusto." Still in shock that he might actually allow me to unload my frustration at my aggressor, I walked over and gave the robber my right fist's most intimate salutation—to the cheering and wild enthusiasm of the two officers.

In hindsight, it was a terrible mistake. These low-profile criminals never end up spending more than one night in jail. Hitting him was a mindless gamble with my own life. César, who knew this more than me, was begging the chief to plant some cocaine on them so they could lock them up longer. They told him they would see what could be done. The next day at work, everyone told me to watch my back. If they were out, these guys would probably come after me. A co-worker of mine let me know that being a foreign, white girl and hitting him in front of his friend were four valid reasons to have me killed. His reputation, you see, had just been subjected to the highest form of embarrassment.

In the month that I spent in Antigua, I learned a lot more about Guatemala than I did touring the whole country. I met countless women, wives, and mothers who had been cheated on, beaten, who had had enough but had no exit. I worked long hours and I made less in a day than what I would make in an hour in New York City. Some 90 percent of my Guatemalan friends had gone to rehab for alcohol or cocaine, including my 20-year-old roommate who was interned in a jail-rehab after being caught with crack when he was barely 16 years old. I was confronted with the worries that Guatemalans have, even in a relatively safe city like Antigua. I did not go to Central America to relax on the beach, so spending a little more time in one spot in order to absorb the culture was a great addition to my trip.

With a little more than a month left in Central America, I hit the road again. This time, I was traveling solo. Before I left, I shared my concerns about traveling alone with Jorge, a 26-year-old dreadlocked Spaniard who'd been living in Mexico for two years. I met him at Ricky's, a bar right off the central park of Antigua, where he was working as a bartender for two months. He was mainly sharing his travel plans and philosophies with me while I listen to his ambitious itinerary. He was on his way south, all the way to the tip of Argentina. He told me traveling alone was the best thing in the world. "The bad moments will be really bad, but the good moments will be the best!"

After my sedentary hiatus, I was eager to see some new lands and get more of that adrenaline-fueled life on the run. Being accompanied by someone didn't really matter at this point. Except when I was on my way to the Salvadoran border and it was getting increasingly dark out. In Escuintla, a big transit town, I had been warned not to travel at night. But, warded off by the steep nightly rates at the town's hotels, I decided to get as close as I could to the border. The bus was slowly unloading its less scary passengers, leaving me alone in a group of toothless gangsters. When the last three girls got off the bus, a series of catcalls trailed them until they were out of sight. I was now the only girl on the bus, never mind the only extranjera in there! I took out my Swiss army knife and inconspicuously opened it before I hid it in my right sweater sleeve. In this very moment, I thought about my sister. Sure it would be better to be traveling with a guy, but at this point almost anyone would do to prevent my imagination from marinating in cautionary tales about rape and murder. However, escaping this "bad moment" generated an immediate "good moment" where a sensation of relief took over. I figured the solo adventure had to start rough to make the rest of my trip look like smooth sailing, despite the little annoyances that might come my way. This was of course a big delusion. I was, after all, a girl traveling with an extremely frugal budget and no guidebook.

To avoid tourist traps and still get to see the sights, I'd ask locals and seasoned travelers for tips. A Peace Corps volunteer who hosted me in San Vincente for two nights recommended the lake of Coatepeque, in the Northeast of El Salvador; a dormant volcanic crater where the breeze was fresh and the water was cool. Even though it meant going back North, and passing through San Salvador again, I took his advice. Lakeside, I woke up at 6 a.m. the next morning, bothered by the mosquitoes. I grabbed my iPod and portable speakers and went out to the dock to catch the sunrise. There was no one around. Not so much as the shadow of a moving thing. I watched nature rising under the sun, while Lou Reed sang "Take a Walk on the Wild Side" in sync with the waves gently rolling in. The sight of water had also made my day eight weeks ago when I was on the Northeast side of Guatemala, in Rio Dulce. But it was different here. There were no sailboats, no packed hostels and loud backpackers. I had an unobstructed view of a chain of vivid green hills, with their tips disappearing into the thick morning clouds. They themselves were so low; I felt I could almost touch them. I had a cigarette, took in the moment and reflected on the past two months. I had traveled through a lot to get to a place like this. But if I only experienced places of this caliber, it would've been lost among a plethora of idyllic sanctuaries. No, this one stood out. And I deserved it. I paid my dues with dodgy little towns and dirt roads sparkling with litter. I thought of what Jorge had said. I'd imagined I'd want to share this kind of moment with someone. But I was alone... and it felt good. I didn't need anyone there. I felt an overwhelming sensation of serenity. I was happy in silence and solitude.

Unfortunately, you can never be totally alone. And female travelers are subject to being followed and spoken to by an endless flock of leeching suitors. And, just like that, the bubble of serenity disappears. It's not like I turned into a hermit after my sister left. I actually stayed in the outskirts of San Salvador for a week with a new crew of friends and had a great time. The fact that I was traveling alone allowed me to stay longer than I had planned. I was able to make completely selfish decisions without hurting anyone. Also, I could plan minimally before making a move. Sometimes, I wouldn't decide where I was going until I reached a bus terminal. That's how I ended up in Honduras.

On my way to the Eastern terminal of San Salvador, Central America's most dangerous capital, my thoughts were boiling. So far, the tentative itinerary was to push further south to Nicaragua. I was discouraged to go to Honduras because of the recent coup. But then again, I had also been warned not to go to the Eastern terminal of San Salvador. When I arrived there, I figured it would be a shame to skip the world famous Bay Islands of Honduras. I wasn't as concerned about the danger of the region as I was about the chunk this detour would be carving into my budget. But I'd heard romanticized stories about the "best beaches in Central America" and cheapest scuba diving worldwide with a chance of seeing whale sharks. I couldn't pass this up. I wouldn't. So I took the bus to El Poy, El Salvador's Northern border with Honduras. I was trying to reach La Ceiba, where I would take the boat to the Island of Utila. By the time I arrived in San Pedro Sula, it was around 7 p.m. I had apparently missed the last bus to La Ceiba. It was already dark and there were no more buses to the center of San Pedro Sula either. Staff at the bus terminal told me that if I were to go to a hostel, I'd have to pay for a cab, the hostel, and another cab back in order to get to the station for the 5 a.m. bus. They estimated the cheapest accommodation would be around 200 lempiras (about $10). I didn't believe that was the cheapest hostel I could find. This is where a guidebook would've come in handy. I begged the guys to look up a cheaper hostel for me because I was broke and couldn't afford to drop 200 lempiras for a night. One of them said I could just stay in the station's waiting room for the night. He said it would be safe because it's guarded by viligantes and there are always other people waiting for early connections. He also mentioned in passing that there was a high chance my cab driver would try to kidnap me on the way to or back from the city. This information helped solve my previous predicament.

Although I had been told that it was safer to stay put, I later learned it didn't mean I'd actually be safe. And, in a situation like mine, the difference between the two leaves room for an unpleasantly varied list of potentially rogue scenarios. I was fine with the illiterate campesinos, who smelled pungently of labor, a smell that would linger for hours after they'd left. I was fine with the group of tattoo-ridden machos off to obscure business in Guatemala. I was even fine among the toothless locals freshly deported from the U.S. What I wasn't fine with was the vigilante I was left with at midnight, a man who twirled his fingers around my backpack straps while progressively decreasing the vital space between us. I felt threatened in a sexual sort of way. In Central America, cops are what people fear most—more than kidnappers, rapists and murderers. The police often belong to all of the above categories. I too, feared them. I started to beat myself up. Mainly because I understood the situation was not OK, and that there was relatively little I could do. My temporary solution was to keep moving around. This would mainly prevent me from going to sleep in a station full of deviants. I did this until 3 a.m., when I spotted a couple with a baby. I figured there would be a good chance that that man wouldn't rape me. When 5 a.m. rolled around, it was time for me to catch my bus. I'd made it through the night. The funny thing is, that night wasn't even the worst thing that happened to me while in Honduras.

The trouble I went through for the sake of that island was worth it. With an ambient temperature of 80ºF accompanied by a cloudless blue sky and a crystal clear sea, it was no wonder I had immediately forgotten how I got there. I was exhausted from the journey over here and the lack of sleep, but jumping in that water made up for the preceding 24 hours of traveling inferno. The water was as calm as a pool. I would swim out 20 meters from the shore and float around for a while. My only focus was to adapt my breathing patterns just so my face would never have to sink below the water. Since the first jump into that transparent sea, I was transported back to my solitary sanctuary.

When I left the beautiful island of Utila, I was in terrible shape. I had a high fever, teary eyes and a relentless migraine. I wanted to see a doctor because I diagnosed myself with swine flu—to the doctor's relief, it was only Malaria. I decided ahead of time to break up this long journey into two days of traveling. I was conscious of the fact that it would be impossible to cross Honduras all the way to Nicaragua in a day. I would probably end up in a border town hotel again, or worse, an abandoned bus terminal. Conveniently, a British girl I'd met on the island needed to stop in Tegucigalpa as well. She had a flight out early the next morning. So we decided we'd head down together and split the cost of a hotel. The bus left La Ceiba at 4 p.m. and arrived in Tegucigalpa at midnight. Now, as I'd learned from previous experience, it's a bad idea to be out and about at midnight in any Central American capital. Add the recent coup d'état to the normal level of danger and you're running some serious risks.

We arrived in the sleeping capital and had no choice but to take a cab. My general rule of safe travel was to take buses whenever possible. They're always safer (once again, not actually safe). We gave the cab driver the name of the hotel we wanted to be taken to and he said he knew it. He quoted a price, which I bargained down. I wasn't concerned about the couple lempiras I would be saving. As a foreigner, if you make habit of paying everything without putting up a fight, the locals will know to rip you off. We drove for 10 minutes before two men emerged from the woods, walked into the middle of the highway and tried to hail our cab. This felt set up. I told the cab driver to keep driving. "No se preocupa, son amigos," he said not to worry, with a smile, they were his friends. I told him that his friends had no business being out here in the middle of nowhere past midnight. If he wanted to pick them up, he was dropping us first then coming back to get them. He tried to argue his point. I replied that the minute they'd touch the door we'd be out with our bags without paying him and that if he didn't start driving instantly, we'd already be on our way. The driver sighed with a smile of malice. Without uttering a word, he simply started the car all the while keeping his eyes set on mine. I understood what he was trying to do. He understood that, too.

I didn't know how common this practice of robbing people in taxis was until I told the story to several Nicaraguans who warned me to stay on my guard in their countries as well. It's called a "Secuestro Express" or Express Kidnapping, and it consists of hijacking people's taxis, threatening them with weapons and stripping them of their possessions. Depending on how greedy they are, they can take everything you're carrying including you backpack full of nothing but dirty laundry. And if they're ruthless, they can ask for your credit card's pin numbers and drag you to every single ATM booth they can find to max out your account. And after all is said and done, even if their booty is substantial, they still might kill you.

This close call prompted me to buy a machete. Not with the intent of slicing someone's head in two, but to deter people from approaching me. The chief accomplishment of this machete, which I carried proudly on the side of my backpack, was that it reduced the machos' catcalls from overwhelming to non-existent. Some testosterone-charged males let me know that it was inappropriate for a young girl like me to be carrying a two-foot machete. I replied that I needed it for the coconuts. And I wasn't exactly lying. In Southern Nicaragua and Costa Rica, I would rarely buy water. I had a plastic bottle, which I regularly topped up with fresh coconut water. When money was tight, I perfected my machete throw so that I could catch bananas as well. My aim was far from perfect; my head swelled with pride even when I caught half a banana. When I first started, I would run in the opposite direction of my throw, afraid that the machete might boomerang back. I came a long way.

I did stop to think about the sharp behavioral turn I had taken during my trip. I had started off being taken care of by my sister and somehow ended up climbing coconut trees when I got thirsty on the beach. When Nastassia was still traveling with me, I didn't need to do anything because she always had the situation under control. While we were together though, I never saw things get out of control the way they sometimes did when I was alone. But I'm not devaluing the little things I picked up while we were together. We only ever took local transportation instead of tourist shuttles and that is something I kept up during the whole trip. Some of her budget-saving techniques I have since mastered—sometimes even improved. She gave me a great foundation for keeping myself together, and I just picked up new stuff along the way. In the end, she helped me "wing it." I did the best I could with what I knew, what I had seen, and what I could do. At the airport, reluctantly on my way out of Latin America, I wondered what she would think of the traveler I had become. As I tied my own backpack straps together, I tried to imagine where I would have been if she had joined me at the end rather than the beginning of my trip. Lost in the jungle? Kidnapped and held for ransom, a picture of me flickering on the nightly news? Those are all fair assumptions.