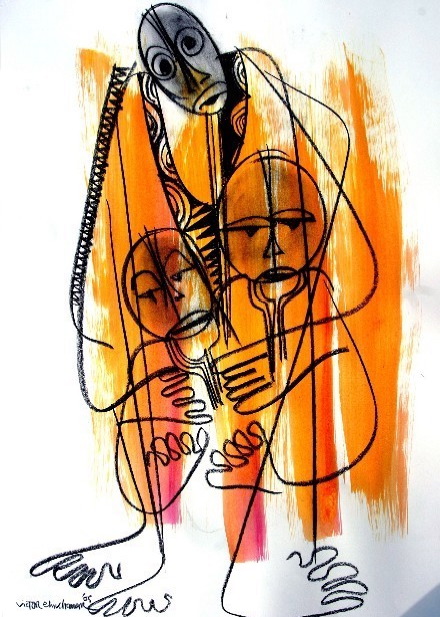

Art by Victor Ehikhamenor

My house had a thatched roof, and our floors were grey mud, caked with dew in the morning. When my three brothers and I woke up, moisture marked where we'd slept as if we had been murdered and the police had chalked the outline of our bodies. My brothers took care of sheep, and I gathered firewood and tended to our garden since I was the only girl. Every Friday, we'd all wake up at sunrise and walk to the market. If we walked along the road for about an hour, we reached the market when it opened and made bargains with the merchants. Then, we'd set up our own piece of plastic tarp on the side of the road, outside the market, and sell vegetables from our own garden so we could afford some meat. At the end of the day, when the merchants were about to close their stalls, we'd make them cheaper offers than the morning and leave home with bags of produce—a lesser quality, but a greater quantity.

One Friday morning a group of three men and one woman came to our village. They'd made a lot of noise outside, slamming their truck door and talking loudly. We were sitting in the back, eating breakfast. The woman, with blonde hair under her safari hat, wearing shorts, tried to speak to us.

"Jambo?" she said. The men stood behind her, smiling, their ironed t-shirts tucked into their trousers.

My brothers ignored her and sipped their tangawizi tea. I finished the roasted piece of breadfruit I was chewing.

"Excuse me," she continued, bending down as if we were ants under a magnifying lens. She cleared her throat and looked back at the men, who gave her apologetic looks. "We want to offer you some dawa. Some medicine?" she asked. "Dawa?" she repeated.

My first brother took an orange from our wooden plate (the one I used to clean rice) and offered it to her. Then he went back to sipping his tea. My second brother asked me how many buckets of tomatoes I'd be able to spare for sale in the market. The woman stared at the orange in her hand, and she walked back to the men, who wore sunglasses. My third brother demanded I pay attention to the matter at hand.

"How many buckets?"

I told him two.

Then the lady came back. We'd heard stories of liars of her kind. How they came to villages and promised to give, started projects, but instead left behind bad smells and filth, messes that wasted our time trying to clean up. It was pure trickery.

"Mimi," she said, pointing to her neck. "Catherine." And then she held up the biggest needle I'd ever seen, tall and skinny, right in front of our noses. My first brother ordered the two others to usher me into my house quickly.

"We are leaving right now," he yelled as they pushed me into the house, almost knocking a pile of firewood over. I heard my first brother screaming above my own questions of "How will we escape?" and "What if they come inside and steal our food?"

My third brother looked at me as if I was the most stupid girl in the entire village. "Food?" he whispered. "Worried about food?" He shook his head. Then my second brother, the talkative one, said, "Worry they won't come and steal you, or your soul. You foolish girl. You could be dead tonight if it weren't for us."

It was true. I wasn't thinking. The vehicle, the one they'd arrived in, totally controlled by them, had killed numerous animals and even some family members. I'd seen it time and time again. They laughed as they drove by and ignored our childrens' waves. Most of the wise elders told stories of those types of people and the land they came from—one filled with hallucinations, evil, and ugliness. They raped and pillaged God's earth.

"Go get the baskets," my second brother ordered me when my first brother came inside, shaking his fist.

"I did it!" first brother exclaimed, more with a tone of anger than of victory. "I scared them away."

We crouched in our hut and watched from a hole in our roof as they drove off. A thick fog of red sand filled the air behind them.

We informed the village leader on our way to the market that someone should keep an eye on our hut in case they came back.

That day, we sold all of our tomatoes. We were able to buy a dozen eggs for only 900 shillings. And the butcher even gave us a handful of meat for free.

When we arrived back home, we carefully checked our hut for intruders. It was as clean as a sanded cow horn. That night, among the sound of howling lions and croaking frogs, my brothers and I slept in peace.